Keeping Our Locomotives Clean

‘The Daves’ are one of a number of the National Railway Museum’s volunteer teams. Called after

the first name of the majority of its members, this band of six volunteers undertakes locomotive cleaning for special events as well as for many private owners around the country.

The team’s latest achievement was cleaning the visiting locomotives for Mallard 75. This was quite something considering they needed to get all three visiting A4s into as near museum condition as is possible. This was despite short time scales and unfavourable weather conditions. Nevertheless, the team managed to get everything done in time for them to be shunted into place. Never ones to take it easy, the team then progressed onto spending their evenings cleaning all six locomotives in preparation for the following morning’s photography sessions. I’m sure you’ll agree, the A4s looked resplendent and we received many favourable comments from the general public on how clean they were.

The next time you see a privately owned locomotive in the museum, or out on the main line, there’s a good chance it has been cleaned by The Daves. This team, comprising David Hurd, David Peaker, David Lowther, David Rush, Ken Chadwick and Alan Papworth, are just one of the many unseen volunteer groups that operate in our museum.

The Importance of Balance

Often as a volunteer manager I find myself trying to meet the contrasting needs of my organisation, my staff and my volunteers. Where projects work best is when the needs of these three parties are all being met and are in balance. When this doesn’t happen, and one group’s needs are placed above the others, that is when problems arise.

For me, the various needs break down a bit like this:

The Organisation

The organisation should have a clear vision about how it involves volunteers and should utilise them in a way that helps it achieve its aims. However, the organisation must be flexible enough to understand the varying needs of its volunteers and react accordingly – providing socially rewarding experiences that benefit both the individual and the organisation.

The Volunteer

Volunteers should be involved in projects which support the museum’s aims and which allow them to fully utilise their skills. These projects should be well managed and rewarding – be that socially, mentally or physically.

Staff

Staff should involve volunteers in projects that help them achieve their aims, but they should be prepared to set aside time and money to manage their projects in the same way that they would manage staff activities.

Put simply, we should strive to create well managed volunteer projects that allow organisations to achieve their aims and which provide the volunteer with wholly rewarding experience….easy! Put another way, balance is just as important to a well run volunteer programme as it is to your daily life. Without it, you’ll probably fall over and so will your volunteer programme!

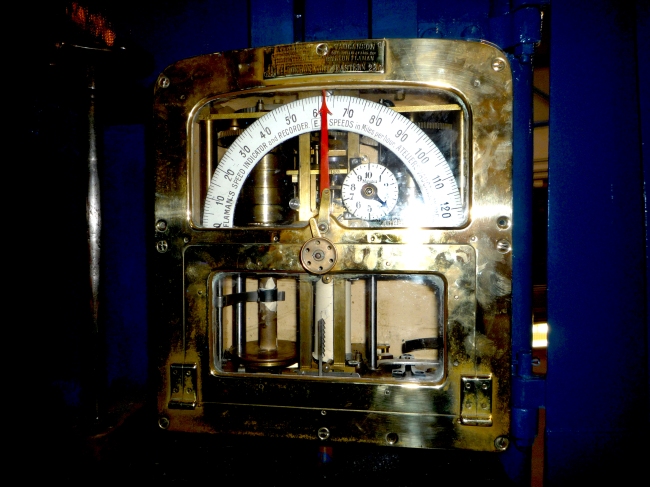

Flaman Speed Recorder

For a long time, most of the world’s railway locomotives were not fitted with any kind of speed indicating device. In France, however, Nicolas Flaman designed a unit which was fitted to most French locomotives even before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Eventually, these same recording devices were fitted to British locomotives. One was fitted to Mallard and was no doubt studied with interest on 3 July 1938, when it would have shown a maximum speed of just over 126 miles per hour. It is still in place in the cab of our locomotive and you can see another example in the Warehouse.

Keith Taylor, Information Point Volunteer

Model students mark world record for Signal School Railway

March 2014 found Students of Carr Junior School, York, helping the NRM celebrate a world record, when the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway School of signalling display was officially named as the world’s oldest working model railway.

Volunteer Peter M Webster, helping Carr students signal trains.

Built in 1912, the model was used until 1995 to train railway workers in the rules and regulations of railway signalling. Since 2003 its been restored to working order by a team of dedicated volunteers and today its still doing what it was designed to do, teach people how to signal trains.

The story began in 1910, when the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway established a ‘School of Signalling’ on the upper floor of its headquarters in Manchester Victoria Station. The school enrolled 100 students, who, as now, attended in their own time, to learn absolute block signalling.

Built in 1912 and still training young signallers.

The experiment was successful enough for a working model railway to be commissioned and installed in the classroom. The model was built as training exercise by apprentices of the company’s Horwich works and supplied with rolling stock by Basset Locke Ltd. It was installed in 1912; and in use by1913.

The newly installed model had working block instruments, interlocked mechanical lever frames and electrically powered trains. It replicated in miniature every situation railway signallers were likely to encounter. In the following 82 years of service, it changed to reflect the railway its students worked on. Overhead wires (catenaries) were added, colour light signals appeared and a train control desk was built. However, despite these changes, it remained a vital training tool for signallers.

In 1995, Rail Track called time on the Edwardian masterpiece and its long working life came to a finish. The layout was donated to NRM and over four days in September 1995, it was packed into boxes and transported to NRM.

Bob Brook (NRM Volunteer) holds the world record certificate

In 1999, Bob Brook and some fellow volunteers began the painstaking process of unpacking the boxes and restoring the model to its former glory. This was a painstaking process, but slowly the team pieced the puzzle back together and made the trains roll again. By 2003, the layout was working again.

Richard Pulleyn (NRM Volunteer) helps the students keep the trains moving.

Today, the model is demonstrated to museum visitors, used by Network Rail and offers hands on signalling experience to school students learning about railway safety. It is a living object that links the museum with 100 years of railway tradition and now a world record holder.

The original L&Y volunteers Bob Brook, Peter M Webster, Len Green Horn and David Eastoe with the world record certificate.

The original L&Y volunteers Bob Brook, Peter M Webster, Len Green Horn and David Eastoe with the world record certificate.

In celebrating the record, it’s important to remember the pioneers, who laid the foundations of success. Therefore, it is a big thanks to Dave Eastoe, Bob Brook, Len Green Horn and Peter Munthe-Webster for laying the foundations that made this record-breaking achievement possible.

Involving “Expert” volunteers

Between 2012 and 2013, our Associate Curator of Railways, Russell Hollowood, worked very closely with one of our Signalling School volunteers, Richard Pulleyn, on a project that would enhance our understanding of our signalling collection. The following blog was written by Richard during the project and highlights the importance of involving groups of “expert” volunteers in your museum’s projects.

At the 2011 Signalling Records Society spring meeting there was an appeal for volunteers to help with identifying the origin and importance of signalling items in the National Railway Museum’s collection. Happily, a number of members came forward and a series of visits were arranged.

Signalling Record Society volunteers (left to right) Andy Overton, Edward Dorricott, Richard Foster, Reg Instone, Charles Weightman, Steve Sharpe, Pete Burke and Richard Pulleyn. Image courtesy of Richard Pulleyn.

By early 2012 most of the signals, lever frames and power signalling equipment that were accessible, recorded, and evaluated. After a careful review of this work, the museum then began deaccessioning duplicated items and those that were incomplete or considered to be of little historical value.

The majority of the remaining collection is now held in the Science Museum Group’s storage facility, at Wroughton. A small proportion has remained at the museum and can be seen in the Warehouse.

Since the move, further equipment has been identified as in need of identification and evaluation. A new group has been formed to work on this and ultimately we hope to produce a comprehensive listing of lever frames and their locations, starting with those at the museum and then expanding to include those held by other organisations.

My Favourite Object

At the National Railway Museum not only do we have a wonderful collection of objects, we also have over 360 amazing volunteers. They support our work in a variety of ways, from assisting with research to running our miniature railway. We value their input tremendously and it’s important to us that they have a strong voice within our organisation. One of the ways we do this is through our “My favourite object” posters. Each month a volunteer writes 100 words on their favourite object from our collection, these are then displayed throughout the museum. As well as providing our volunteers with the chance to share their passion with our visitors, it has also proved a fascinating and personal way of interpreting the collection.

Since we started, almost two years ago, we have displayed a huge range of objects. My personal favourites include a story about the parents of one of our volunteers travelling on Golden Arrow and one man’s affection for a station bench!

Each month I’ll be sharing one of these stories with you. If you have any personal connections with the objects please let me know, as I’d love to hear them.

THE ALAN JACKSON ARCHIVE

Background

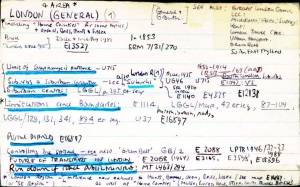

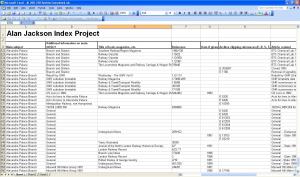

Alan Jackson was an inveterate collector of information on all aspects of the railways and recorded his data on a series of index cards. He left his collection of cards and supporting material to the Railway and Canal Historical Society and they have passed them to us at the NationalRailwayMuseum. The cards have been digitised and a team of volunteers is entering the hand written data into Excel spreadsheets. When this lengthy process is complete, the data will be transferred into the Museum’s systems, to form an invaluable archive, available to specialist and general users.

The Role

As one of our volunteers you’d receive batches of up to 50 digitised cards, together with a prepared spreadsheet and guidance notes on how to transcribe the information. Included with this is reference material to explain the codes Alan Jackson used. A digitised card looks like this:

and, when transcribed, the spreadsheet looks like this:

We need

Many more transcribers, to help us move this project forward

Transcribers need

- A computer with a good sized monitor, Windows 98 or later, and Microsoft Excel

- A broadband link to receive and transmit files

- Reasonable keyboard skills

- A willingness to sit the computer for blocks of time, capturing data

and some knowledge of railways can he helpful

Does this project interest you? If so, you can find a simple application form here

An Alternative Approach to Motivating Volunteers

Over the last five years volunteering at the National Railway Museum has increased by 167%, but why? What is it that motivates people to come in and sit at an information desk when the museum is almost empty or to stand in the pouring rain waiting for customers for the miniature railway? If we look at the results from last year’s Science Museum Group Survey we see that initial motivators vary greatly, from an interest in the subject to being given a CV boosting experience. But although this might explain why people begin volunteering with and, perhaps, indicate to some extent why they stay it doesn’t provide us with a comprehensive answer. Of course, as good volunteer managers we would be foolish to ignore this information and we should always strive to create volunteer programmes that responds to the needs of our volunteers and that we ourselves would wish to be a part of. But how can we move beyond just doing what our volunteers tell us they want? How can we be proactive instead of reactive?

In his book, Drive: The Surprising truth about what motivates us, Daniel H. Pink offers us one possible solution. He suggests that traditional carrot and stick motivators such as rewards, punishments and target setting are not only inefficient ways of motivating people but can, in fact, have a negative effect. So how does that affect us as volunteer managers? Well, probably not that much. The traditional ways that business applies these standards – target related bonuses and pay reductions – don’t really reflect what we as volunteers managers do. However, what Pink goes on to say is important and highly relevant. He suggests that instead of using carrot and stick motivators we should be empowering our staff – or in our case, our volunteers – in three distinct ways: vision, mastery and autonomy.

- Vision: We should ensure that our staff can see how their work contributes to the overall achievement of an organisation’s vision.

- Mastery: We should empower our staff with the skills they need to master their work.

- Autonomy: We should free our staff to make creative decisions that allow them to apply their skills in a way that lets them make a maximum contribution to the vision.

For us as volunteer managers, this philosophy could prove a vital tool in unlocking the potential within our volunteer programmes. Yes we need to get the basics right: we need to make our volunteers feel a part of our organisation, we need to make them feel valued and we need to respond to their needs. But beyond this, we need to consider applying Pink’s philosophy. That means trusting our volunteers, empowering them to make choices and being creative with the roles we develop. Ultimately we must try and ensure that roles are worthwhile and contribute to our organisation’s aims, that volunteers are given freedom within their roles and that we give them the opportunity to develop and fully master what they are doing. If we can do this then we can fully unlock the potential without our volunteer programmes.